I posted this picture of the 38th Dogras and the 25th Cavalry (Frontier Force) parade through Lahore, 1909 on Facebook and Twitter this week. Someone on Twitter pointed out that the officer on horseback in the centre of the picture was named but it was difficult to make it out.

The 38th Dogras and the 25th Cavalry (Frontier Force) parade through Lahore, 1909 NAM. 1969-10-587-1-28 (1)

I decided to see if I could find out the identity of the unknown officer. First port of call was the Army and Navy Gazette, I knew he was a captain but wasn’t sure which of the two regiments he belonged to, so I used the search terms Captain, 38th Dogras and 1909. After searching through the first few results, it became apparent that none of the officers named matched the caption.

I next tried to search the terms Captain, 25th Cavalry and 1909. After working through some of the results a name came up that seemed to fit. It was an entry in the Army and Navy Gazette of a Captain George Chrystie of the 25th Cavalry being appointed to the Kurram Militia wing commander. (2)

This surname seemed to fit so I decided to see what else I could find out about the officer.

George Chrystie and his twin brother, John were born on the 9th March 1872 to Colonel George Chrystie and Helen Ann Thomasina Myers. They were baptized on the 6th October 1872 in Masulipatam , Madras. (3)

He was born into a family who had spent generations serving their country and his great-uncles. Lieut. John Chrystie. R.N., and Capt. Thomas Chrystie, R.N. served under Nelson. The former was in the Victory immediately before Trafalgar, but was transferred on promotion. The latter was at Trafalgar in the Defiance.

Born in India both boys were educated in England, first at Surrey County School and then Craideigh and Portsmouth Grammar School. They then both joined the British Army though in different roles, John joined the Artillery and George was gazetted a 2nd Lieutenant in 1st Royal Dublin Fusillers on the 18th June 1892.

He was promoted to Lieutenant on the 25th June 1895. Chrystie seems to have been an excellent solider and on the 23rd October 1896 transferred to the Indian Staff corps and a year later was appointed to the 5th Punjab Calvary (as 25th Calvary was then designated). In 1901 he was promoted Captain and in 1910 to Major. (4)

He was married to Melver Campbell and they had three daughters, Aileen Margaret, Elizabeth Frances and Alice Helen. (5)

In 1913, Captain Chrystie and his regiment were based in and around Bannu (The town was founded in 1848 by Herbert Benjamin Edwardes) which is in Modern day Pakistan and was used during the Raj as as base for action against Afghan border tribes.

On the 29th April 1913, news came into the town that there had been a raid at Isa Khel, about 35 miles South of Bannu and that the raiders had carried off four Hindu boys and were making off for the passes to the North East.

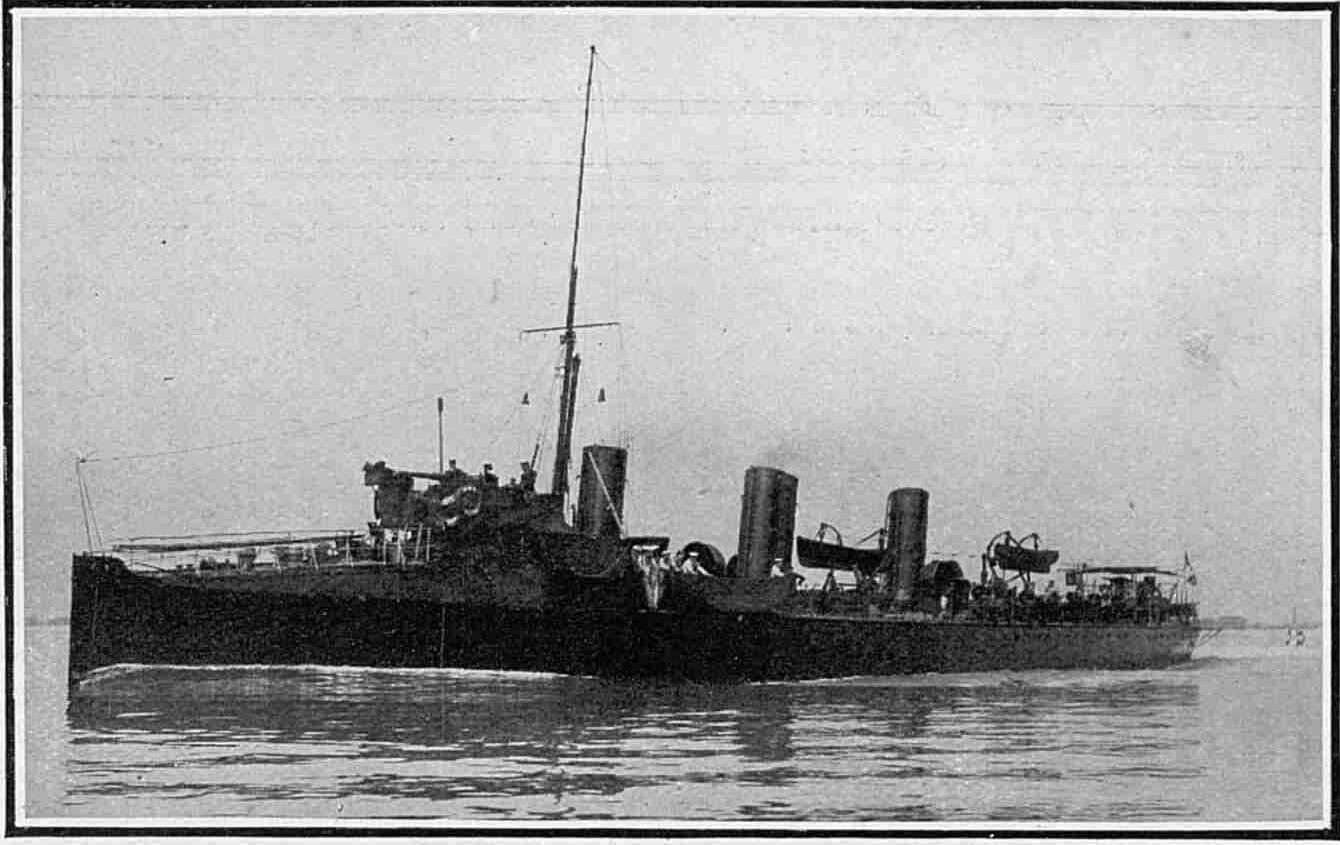

Possibly Captain (later Major) George Chrystie?

A brother officer then describes the action.

At 11.30 on Thursday we were in office when news came that the raiders had been seen at Naurang, about 12 miles south, that morning. Immediately two squadrons went out, Major Chrystie with B to Naurang, and Grant with A to Jani Khel, to hold the nullahs to the west in case they should try and break back. Two companies of Coke’s Rifles also went to Naurang. When Major Chrystie got to Naurang on Thursday he found the raiders had been sighted early that morning, but had got away from the police, and had gone off to teh east followed by the police and villagers. So Major Chrystie went after them and soon caught up and passed the police and halted that night, having done 5 1/2 miles with barely a halt.

On again at dawn Friday, over a bare waterless country with everything against him, and everything in favour of the raiders, but he stuck to it all that day and by 4pm reached teh edge of the Salt Range, 30 miles to the East of Bannu, having done over 100 miles since noon the day before. Then he lost trace of the raiders among the infernal Salt Hills and was just turning towards home, when he heard firing, and found that the Salt Mine Police had sighted the raiders, so he divided his squadron and sent half to head them off, and at last ran tehm to earth in a nullah.

You must wonder why, having surrounded these fellows, he did not at once go in and finish them off, but you must remember that though one cannot help admiring these fellows for their guts, to use an expressive if vulgar term, they must have done 60 to 70 miles in 24 hours, carrying rifles and ammunition, yet they are such blackguards, with a list against them of the foulest crimes imaginable long enough to hang a hundred men, that one can only look on them as vermin, and as such to be destroyed in the safest way possible, and to rush them in the dark, quick though it would have been, would have meant certain death for at least four or five of our fellows.

The Raiders rushed into this nullah, which had almost precipitous sides of shale about ten to twelve feet deep and they were fired at by our party. Two were killed, the remaining three (there were eight to start with but two were killed before, and one got away) got behind some big shale boulders where they were absolutely under cover. Our people occupied the remaining sides and the forth was held by the police. As they were quite unget-at-able where they were in the dark, the deputy Commissioner, Bill, made big bundles of brushwood and straw and set alight to them and pushed them with a long stick over the edge of the nullah to smoke them out. Major Chrystie from the other side shouted to tell him where to push them, and then they pushed one over another. Those who where with him say that Major Chrystie raised himself on his knees and peered over to see where a bundle would fall, but it stuck on the edge of the slope and flared up, and by its light the raiders saw him and fired at fifty yards and the bullet struck him in the chest and he dropped forward stone dead. And so the dragged him behind the ridge and carried him down to the road two miles away.

Of all the crowd who raided Isa Khel only one escaped, so it has been a fine show as we have had for some time, but it isn’t worth losing a man like Chrystie for all the blackguards in Asia. He was the one man we could least afford to lose, one of the straightest and best men I had ever met, a man you could absolutely rely on, and a jolly good soldier to boot. (6)

As an aside note, the three Hindu boys were recovered and returned to their families. Major Chrystie’s body was carried back to Bannu, were he was buried in his local church. He left all is worldly goods to his wife and Daughters.

The hand written will of Major George Chrystie. (7)

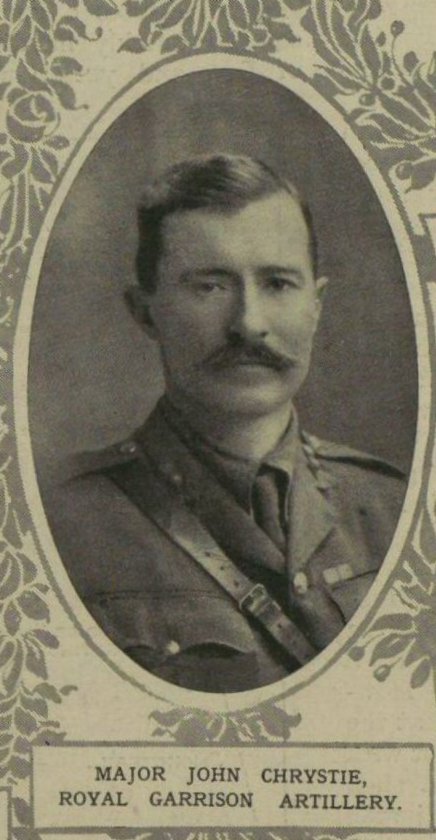

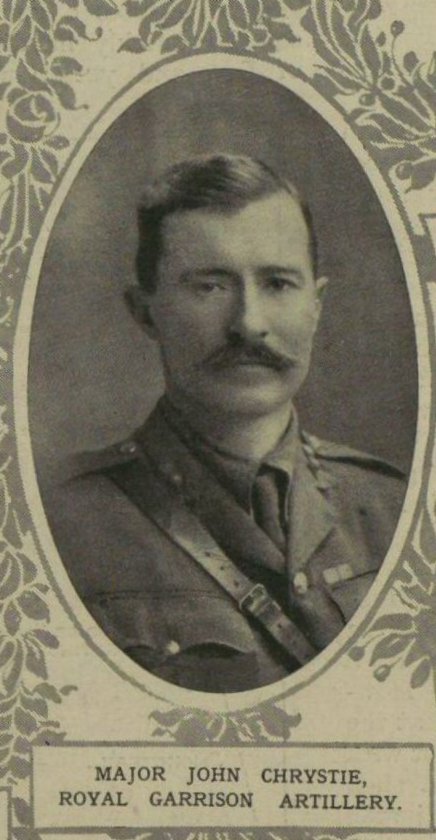

In a final twist of fate for the Chrystie family, his twin brother was killed in action in the First Battle of Ypres at Zillebeke. near Ypres on 17 Nov. 1914; and was buried in Ypres Cemetery.

His colonel wrote of him: He left behind him the lasting memorial of a shining example, of how we ought to live and die, and we shall not forget it. He came to this brigade at my invitation, stayed in it at my invitation, and so far as we all are concerned he remains in it for ever. We shall not see his like any more. (8)

Major John Chrystie

So both twin brothers both died in the service of their country, George in an insignificant action in the wilds of the North West Frontier and John in the killing fields of Belgium during the bloodiest conflict man had ever known but both seemed to have been well liked and respected soldiers.

Both are commemorated on a plaque in All Saints Church, Witley.

Memorial Plaque to the Chrystie Twins. All Saints Church

Sources.

- NAM. 1969-10-587-1-28

- Army Navy Gazette Saturday 05 June 1909 British Newspaper Archive.

- FindMyPast British India Office Births & Baptisms. Record N-2-53 226.

- FindMyPast British Army, Army Lists 1839-1946. Image number: 682.

- Army Navy Gazette 10th may 1913. British Newspaper Archive.

- Army Navy Gazette 21st June 1913. British Newspaper Archive.

- FindMyPast British India Office Wills & Probate. Record L-AG-34-40-73

- masonicgreatwarproject.org.uk/legend.php?id=548

- Surrey in the Great War: A County Remembers